On January 23th, 2020, Christine Lagarde, Mario Draghi’s successor as President of the European Central Bank, announced that the ECB Governing Council is going to launch a review of its monetary policy strategy. A similar measure has been taken in the past; in 2003 the annual inflation target was raised from a range between zero and 2 percent to the current “below, but close to, 2 percent”.

The reasons why this review has been announced are that, since 2003, the euro area, and the world economy in general, has seen structural changes that make it more difficult for the central bank’s tools to successfully pursue its price stability mandate. In particular, slowing productivity and the ageing population in Europe, which have caused growth trends to decline, combined with the 2008 financial crisis have driven interest rates down, even below the nominal zero lower bound. They have made it necessary for central banks around the globe to adopt unconventional monetary instruments to stimulate GDP growth and to raise inflation, which remains under the desired target.

Indeed, during the years as President of the ECB, Mario Draghi was able to avoid a sovereign debt crisis, but failed to prop up inflation – which has proven much more challenging. Hence the need to review the quantitative formulation of price stability, as well as the (conventional and unconventional) instruments employed until now to reach this objective. In addition to negative interest rates, forward guidance, quantitative easing and communication practices, the ECB aims to include climate change and environmental sustainability among priority considerations in the review process.

Inflation target

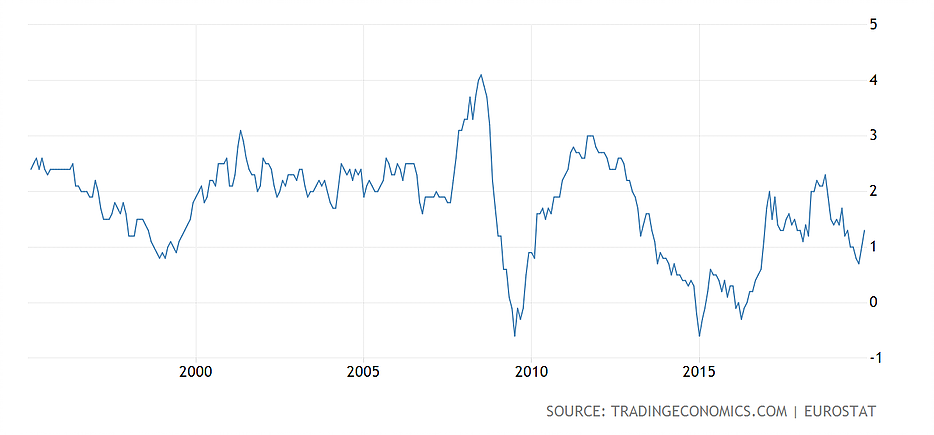

From the following graph, which illustrates annual inflation trends in the eurozone, we see that in the eight years of Draghi’s presidency, inflation averaged just 1.3 percent.

Despite a very accommodative monetary policy, the rate has not been able to persistently meet the “below, but close to, 2 percent” target and some are beginning to question the efficacy of the main tools at the central bank’s disposal.

Economists believe that a new price mandate formulation will be at the core of Lagarde’s strategy review. Many expect the ECB to correct the existing vagueness and to drop the “below but close to” part from the current objective and switch to a clearer 2 percent goal, which would align the ECB to the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, who share such a straightforward goal. In the view of many, a clear point target will be more able than the current ambiguous expression to durably anchor economic agents’ expectations of future inflation to the chosen level. Additionally, a 2 percent goal, being slightly higher than the current one, is harder to reach starting from the lower than optimal inflation we are facing these years. This would also mean that interest rates will stay very low for a longer period of time because the economy needs to be propped up more in order for inflation to get to this higher target.

In the view of many economists, the inflation target should be symmetrical, meaning that the ECB should be concerned about inflation going too high as much as going too low. This principle, albeit not formally approved by the Governing Council, was adopted by Draghi in the final moments of its presidency, when in the usual press conferences after his last monetary policy decisions he affirmed the ECB’s commitment to symmetry around the inflation aim. It is important to have an upper bound for inflation, as well as a lower bound, to better manage price setters’ expectations and avoid prices to rise too rapidly following periods of higher than expected production or demand growth.

Other economists believe the choice should fall on targeting a band instead of a single number. A proposal by the president of the Dutch central bank and supported by Germany, suggests a band of 1.5 to 2 percent. This would cause a reduction of the ECB’s objectives and is criticized for the fact that it would effectively target a lower inflation level, leaving the ECB with less leeway to make real interest go negative in the future. Indeed, the higher inflation, the easier it is for rates to go down and have a positive effect on the economy.

An alternative proposal is to shift the inflation target to a band of 1.5 to 2.5 per cent, which would give the ECB more flexibility to accept periods of either high or low inflation.

Negative rates

The ECB introduced negative interest rates in 2014 as an extraordinary measure to stimulate the eurozone economy. Their use has had some downsides (which we will discuss in this section) though, and that is why the ECB will probably try to assess whether these downsides exceed the benefits in terms of growth and may decide to provide some guidelines on how to use this instrument and achieve the minimization of the negative effects at the same time.

Let’s see what negative interest rates are exactly and their main purposes. At the moment, the three main rates are -0.50%, 0.00% and 0.25%. The negative one is the interest rate on the ECB’s deposit facility, which is the rate banks earn (or pay, if negative) on the liquidity they keep at the central bank. The decision to introduce negative rates was particularly contested in Germany, where Mario Draghi was nicknamed “Count Draghila”, a vampire who strips savers of money in their bank accounts.

In principle, negative (or very low) rates should discourage commercial banks from leaving money in their accounts at the ECB, as they would not only earn no profit on them, but would instead pay a cost (the -0.50%). Therefore, banks are induced to lend at low cost to other banks, firms and consumers, in turn pushing all economic agents to borrow and spend more and to save less, which should help economic growth. Negative rates are also able to weaken the national currency (in our case the euro), with the desired effect of helping exports (as these would be cheaper to buy in terms of other currencies) while at same time making imports more costly, in order to fuel inflation. What economists worry about is that prolonged periods of negative interest rates could generate distortions in the economy, on the one hand by encouraging families and firms to borrow too much, on the other by forcing banks to pass negative rates on to their consumers, that is charging to accept deposits, which could lead to a rush into cash.

This is, indeed, what is starting to happen in some countries. In Germany, for example, almost 60% of banks are charging negative rates on corporate clients’ deposits, while more than 20% are doing the same to retail customers.

Another side effect of negative interest rates is that they lead to “zombification”, the situation in which unproductive firms, that would otherwise be dragged out of the market by competition, stay afloat and continue to operate just because of the negative cost of borrowing. As they work on lower markups, they manage to charge lower prices compared to those charged by more productive firms, actually causing deflationary pressures on the economy and undermining the original reasons why negative rates were needed in the first place (to sustain inflation).

Probably fearing these side effects, and an imminent housing bubble, Sweden’s central bank, the Riksbank, recently decided to abandon negative rates. When interviewed about Sweden’s decision, Ms. Lagarde replied that the Riksbank’s rate increase was proof that negative rates had succeeded in propping up the economy and they were no longer needed.

We’ll see if changes to the negative interest rates policy will be made in the strategy review.

Climate change

As we said, Ms Lagarde is calling for climate change and environmental responsibility to be a key part of the strategic review, making the ECB the pioneer central bank in this field. Many are wondering what this might entail from a practical point of view.

There is speculation, following the proposal made by the governor of the Banque de France, that the ECB could start to include climate-related risks and considerations in the evaluation of the collateral it accepts from banks in exchange for liquidity.

Climate-change activists are pushing further and are asking the ECB to review the composition of its €2.6tn asset-purchase program – the quantitative easing policy. In particular, they are requesting that the ECB divest “brown” bonds (those that are issued by carbon-intensive companies) and, at the same time, increase purchases of green bonds (those that are issued to raise capital for climate change solutions). This proposal is strongly opposed by some members of the Governing Council, such as the president of the Deutsche Bundesbank. In their view, decisions related to climate change policies should be made by governments or elected officials, not by central banks.

Nonetheless, the idea is appealing to the European Commission, which has been independently designing a Green Deal with the objective of cutting CO2 emissions. Single market and industry commissioner Thierry Breton recently said that in order to raise the €1tn needed for the Green Deal, national governments might issue long-term bonds that could be (indirectly) bought by the ECB through its quantitative easing program.

Conclusion

A lot of food for thought is on the European Central Bank’s plate. We have seen that the monetary policy strategy review announced by Christine Lagarde will be a comprehensive rethinking of the tools and policies currently adopted by the ECB. We may see changes in inflation targeting, in the use of negative interest rates and in the employment of conventional and unconventional tools in general.

Anyhow, it may take some time before we get a more precise and concrete idea of the changes Ms Lagarde and the Governing Council will adopt for the monetary policy strategy of the euro area. It is an internal process of the Governing Council and we will probably know about conclusions and decisions in a monthly press conference in December or January at most.

Umberto De Vito International Economics and Finance Università Bocconi Milano - thanks to G generation